Each time we build a field validation from scratch, accessibility doesn’t come out of the box. In this guide, Sandrina breaks down what we need to take into consideration, so that nobody gets stuck on an inaccessible invalid field.

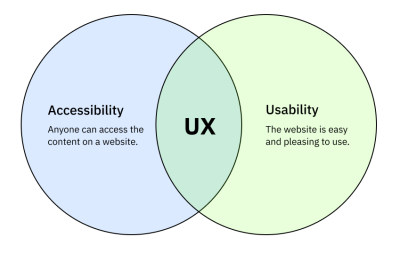

When it comes to form validation, we can explore it from two perspectives: usability and accessibility. “What’s the difference between usability and accessibility?” you may ask. Let’s start from there.

Usability #

Usability is about improving a given action until it’s as easy and delightful as possible. For example, making the process of fixing an invalid field easier or writing better descriptions so the user can fill the field without facing an error message.

To get a really good grasp of the challenges in this process, I highly recommend you to read the deep-dive “Designing better inline validations UX” from Vitaly. There, you’ll learn about the different approaches to validate a field and what are the caveats and trade-offs of each one.

Accessibility #

Choosing the best UX approach is just half of the challenge. The other half is ensuring that any person knows the field is invalid and easily understands how to fix it. That’s what I’ll explore through this guide.

You can look at ‘Accessibility’ and ‘Usability’ as two equally important universes with their own responsibilities. Accessibility is about ensuring anyone can access the content. Usability is about how easy it is to use the website. Once overlapped will take ‘User Experience’ to its best.

With these two concepts clarified, we are now ready to dive into accessible validations.

Table Of Contents #

- Accessibility In Forms

- The Field Instructions

- Required Fields

- Invalid Fields

- Moments Of Validation

- Testing Field Validations

- Things To Keep In Mind

Accessibility In Forms #

Before we get into validation, let me recap the accessibility fundamentals in forms:

- Navigation

The form can be navigated using only the keyboard, so people who don’t use a mouse can still fill and submit the form. This is mostly about setting a compliant focus indicator for each form control. - Context

Each form field must have an accessible name (label), so people who use assistive technologies can identify each field. For example, screen readers would read a field name to its user.

Screen Readers In Forms #

Similar to browsers, screen readers (SR) behave slightly differently from each other: different shortcuts, different semantic announcements, and different features support. For example, NVDA works better with Firefox, while VoiceOver works best with Safari, and both have slightly different behaviors. However, this shouldn’t stop us from building the common solid foundations that are strongly supported by all.

A while ago, I asked on Twitter how screen reader users navigate forms. Most prefer to Tab

or use special shortcuts to quickly jump through the fields, but

oftentimes can’t do it. The reason is that we, developers, forget to

implement those fields with screen readers in mind most of the time.

Currently, many of the field validations can’t be solved with native HTML elements, so we are left with the last resource: ARIA attributes. By using them, Assistive Technologies like screen readers will better describe a given element to the user.

Through the article, I’m using VoiceOver in macOS Catalina for all the scenarios. Each one includes a Copeden demo and a video recording, which hopefully will give you a better idea of how screen readers behave in forms, field descriptions, and errors.

The Field Instructions #

Field Description #

The field label is the first visual instruction to know what to fill in, followed by a description when needed. In the same way sighted users can see the description (assuming a color contrast that meets WCAG 1.4.3 Contrast Minimum), the SR users also need to be aware of it.

To do so, we can connect the description to the input by using the aria-describedby attribute, which accepts an id

pointing to the description element. With it, SR will read the

description automatically when the user focuses on the field input.

The Future Of ARIA Description #

An ARIA attribute aria-description exists, but it’s not yet supported by most screen readers. So, for now, we’ll need to stick with aria-describedby.

The Difference Between aria-labelledby And aria-describedby #

The attribute aria-labelledby is an alternative to <label> and aria-label, responsible for the field’s accessible name. In short, we should use aria-label for critical information and aria-describedby for additional information. The aria-describedby is announced after the label with a slight pause between both. For example, in the demo above, the Voice Over would announce:

{name} {role} [pause] {description}.

“Your address, input [pause] Remember to include the door and apartment.”

How Descriptions Are Announced #

It’s worth noting that aria-describedby is only meant to some HTML elements.

Depending on the screen reader, it’s also announced slightly

differently. Some screen readers allow customizing how long the pause

between the label and description is and even mute the description.

Adrian Roselli has a brilliant deep dive on descriptions exposure across all screen readers. The bottom line is not to rely on descriptions to convey critical information that can’t be easily accessed in another way.

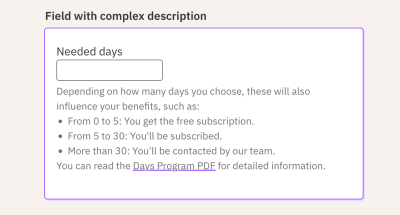

Dealing With Complex Descriptions #

When announcing texts inside aria-describedby,

the screen readers will read it as just plain text, ignoring any

semantics. Imagine a field that contains a long description with lists,

links, or any other custom element:

In this field, it would cause more harm than good to connect the entire description to the aria-describedby.

Instead, I prefer to connect a short description that hints to the user

about the full description so they can navigate to it on their own.

As

this short description is exclusive to assistive technologies only, we

need to hide it from sight users. A possibility could be using the .sr-only technique.

However, a side-effect is that the screen reader user would bump into

it again when moving to the next element, which is redundant. So,

instead, let’s use the hidden attribute, which

hides the short description from assistive technologies altogether, but

still lets us use the node’s contents as the inputs’ description.

I find this pattern very useful for fields with long descriptions or even complex validation descriptions. The tip here is to hint to the users about the full instructions, so they won’t be left alone guessing about it.

Required Fields #

How do you know a field is required? Depending on the context, it might be intuitive (e.g., a login form). Many times we need an explicit clue, though.

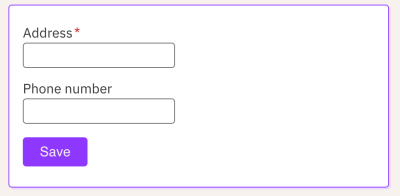

The Visual Clue #

The red asterisk is one of the most common visual patterns, like the following:

Visually most people will recognize this pattern. However, people who use SR will get confused. For instance, Voice Over will announce “Address star, edit text.” Some screen readers might completely ignore it, depending on how strict the verbosity settings are.

This

is a perfect scenario of an element that, although it’s visually

useful, it’s far from ideal for SR users. There are a few ways to

address this asterisk pattern. Personally, I prefer to “hide” the asterisk using aria-hidden="true", which tells all assistive technologies to ignore it. That way, Voice Over will just say “Address, edit text.”

The Semantic Clue #

With the visual clue removed from AT, we still need to semantically tell the input is required. To do so, we could add the required attribute to the element. With that, the SR will say, “Address, required, edit text.”

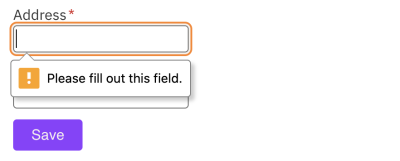

Besides adding the necessary semantics, the required

attribute also modifies the form behavior. On Chrome 107, when the

submit fails, it shows a tooltip with a native error message and focuses

the required empty field, like the following:

The Flaws In Default Validations #

Probably your designer or client will complain about this default validation because it doesn’t match your website aesthetics. Or your users will complain the error is hard to understand or disappears too soon. As currently, it’s impossible to customize the styling and behavior, so we’ll see ourselves forced to avoid the default field validation and implement our own. And just like that, accessibility is compromised again. As web creators, it’s our duty to ensure the custom validation is accessible, so let’s do it.

The first step is to replace required with aria-required,

which will keep the input required semantics without modifying its

style or behavior. Then, we’ll implement the error message itself in a

second.

Here’s a table comparing side by side the difference between required and aria-required:

| Function | required | aria-required |

|---|---|---|

| Adds semantics | Yes | Yes |

| Prevents invalid submit | Yes | No |

| Shows custom error message | Yes | No |

| Auto-focus invalid field | Yes | No |

Reminder: ARIA attributes never modify an element’s styles or behavior. It only enhances its semantics.

As an alternative, if you need to keep the required attribute but without the ‘validation behavior’, you can add the novalidate attribute to <form>. Personally, I still prefer the aria-required because it’s easier to control the input behavior isolated in a Field component without depending on the parent element.

Invalid Fields #

The Color Trap #

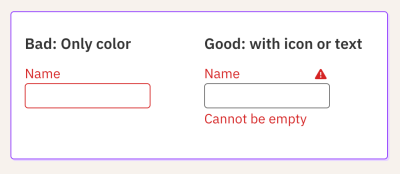

In a minimalist design, it’s tempting to use only the red color to express that the field is invalid. Although the usage of color is beneficial, using it alone is not enough, as defended by WCAG 1.4.1 Use of Color. People perceive color in different ways and use different color settings, and that red color won’t be noticed by everyone.

The solution here is to complement the colorful error state with an additional visual element. It could be an icon, but even that might not be enough to understand why the field is invalid. So the most inclusive solution is to explicitly show a text message.

The Error Message #

From a usability standpoint, there’s a lot to take into consideration about error messages. In short, the trick is to write a helpful message without technical jargon that states why the field is incorrect and, when possible, to explains how to fix it. For a deep dive, read how to design better error messages by Vitaly and how Wix rewrote all their error messages.

From

an accessibility standpoint, we must ensure anyone not only knows that

the field is invalid but also what’s the error message. To mark a field

as invalid, we use the ARIA attribute aria-invalid="true", which will make the SR announce that the field is invalid when it’s focused. Then, to also announce the error, we use aria-describedby we learned about before, pointing to the error element:

Invalid Field With Description #

A good thing about aria-describedby

is that it accepts multiple ids, which is very useful for invalid

fields with descriptions. We can pass the id of both elements, and the

screen reader will announce both when the input is focused, respecting

the order of the ids.

The Future Of ARIA Errors And Its Support #

An ARIA attribute dedicated to errors already exists — aria-errormessage — but it’s not yet supported by most screen readers. So, for now, you are better off avoiding it and sticking with aria-describedby.

In the meantime, you could check A11Ysupport to know the support of a given ARIA attribute. You can look at this website as the “caniuse” but for screen readers. It contains detailed test cases for almost every attribute that influences HTML semantics. Just pay attention to the date of the test, as some tests might be too old.

Dynamic Content Is Not Announced By Default #

Important to note that although aria-describedby

supports multiple ids, if you change them (or the elements’ content)

dynamically while the input is focused, the SR won’t re-announce its new

content automatically. The same happens to the input label. It will

only read the new content after you leave the input and focus it again.

In order for us to announce changes in content dynamically, we’ll need to learn about live regions. Let’s explore that in the next section.

Moments Of Validation #

The examples shown so far demonstrate ARIA attributes in static fields. But in real fields, we need to apply them dynamically based on user interactions. Forms are one of the scenarios where JavaScript is fundamental to making our fields fully accessible without compromising modern interactive usability.

Regardless of which moment of validation (usability pattern) you use, any of them can be accomplished with accessibility in mind. We’ll explore three common validation patterns:

- Instant validation

The field gets validated on every value change. - Afterward validation

The field gets validated on blur. - Submit validation

The field gets validated on the form submit.

Instant Validation #

In this pattern, the field gets validated every time the value changes, and we show the error message immediately after.

In

the same way, as the error is shown dynamically, we also want the

screen reader to announce it right away. To do so, we must turn the

error element in a Live Region, by using aria-live="assertive". Without it, the SR won’t announce the error message, unless the user manually navigates to it.

Some nice things to know about this example:

- While the input is valid, the

aria-invalidcan be"false"or be completely absent from the DOM. Both ways work fine. - The

aria-describedbycan be dynamically modified to contain one or multiple ids. However, if modified while the input is focused, the screen reader won’t re-announce its new ids — only when the input gets re-focused again. - The

aria-liveattribute holds many gotchas that can cause more harm than good if used incorrectly. Read “Using aria-live” by Ire Aderinokun to better understand how Live Regions behave and when (not) to use it. - From a usability perspective, be mindful that this validation pattern can be annoying, the same way it’s annoying when the error shows up too early while we are still typing our answer.

Afterward Validation #

In

this pattern, the error message is only shown after the user leaves the

field (on blur event). Similar to the ‘Instant Validation’, we need to

use the aria-live so that the user knows about the error before start filling the next elements.

Usability tip: I personally prefer to show the on-blur error only if the input value changes. Why? Some screen reader users go through all the fields to know how many exist before starting to actually fill them. This can happen with keyboard users too. Even sight users might accidentally click on one of the fields while scrolling down. All these behaviors would trigger the on-blur error too soon when the intent was just to ‘read’ the field, not to fill it. This slightly different pattern avoids that error flow.

Submit Validation #

In this pattern, the validation happens when the user submits the form, showing the error message afterward. How and when exactly these errors are shown depends on your design preferences. I’ll go through two of the most common approaches:

In Long Forms #

In this scenario, I personally like to show an error summary message, usually placed right before the submit button, so that the chances of being visible on the viewport are higher. This error message should be short, for example, “Failed to save because 3 fields are invalid.”

It’s also common to show the inline error messages of all invalid fields, but this time without aria-live

so that the screen reader doesn’t announce all the errors, which can be

annoying. Some screen readers only announce the first Live Region

(error) in the DOM which can also be misleading.

Instead, I add the aria-live="assertive" only to the error summary.

In the demo above, the error summary has two elements:

- The semantic error summary contains a static error summary meant to be announced only on submit. So the

aria-liveis in this element, alongside the.sr-onlyto hide it visually. - The

visual error summary updates every time the number of invalid fields

changes. Announcing that message to SR could be annoying, so it’s only

meant for visual updates. It has the

aria-hiddenso that the screen readers users don’t bump into the error summary twice.

Check the screen reader demo below:

In Short Forms #

In very short forms, such as logins, you might prefer not to show an error summary in favor of just the inline error messages. If so, there are two common approaches you can take here:

- Add an invisible error summary for screen readers by using the

.sr-onlywe learned above. - Or, when there’s just one invalid field, focus that invalid field automatically using

HTMLElement.focus(). This helps keyboard users by not having to tab to it manually, and, thanks toaria-describedby, will make screen readers announce the field error immediately too. Note that here you don’t needaria-liveto force the error announcement because the field getting focused is enough to trigger it.

Accessibility Comes Before Usability #

I must highlight that this is just one approach among others, such as:

- Error text

It can be just a simple text or include the number of invalid fields or even add an anchor link to each invalid field. - Placement

Some sites show the error summary at the top of the form. If you do this, remember to scroll and focus it automatically so that everyone can see/hear it. - Focus

Some sites focus on the error summary, while others don’t. Some focus on the first invalid field and don’t show an error summary at all.

Any of these approaches can be considered accessible as long it’s implemented correctly so that anyone can perceive why the form is invalid. We can always argue that one approach is better than the other, but at this point, the benefits would be mostly around usability and no longer exclusively about accessibility.

Nevertheless, the form error summary is an excellent opportunity to gracefully recover from a low moment in a form journey. In an upcoming article, I will break down these form submit patterns in greater detail from both accessibility and usability perspectives.

Testing Field Validations #

Automated accessibility tools catch only around 20-25% of A11Y issues; the more interactive your webpage is, the fewer bugs it catches. For instance, those tools would not have caught any of the demos explored in this article.

You could write unit tests asserting that the ARIA attributes are used in the right place, but even that doesn’t guarantee that the form works as intended for everyone in every browser.

Accessibility is about personal experiences, which means it relies a lot on manual testing, similar to how pixel-perfect animations are better tested manually too. For now, the most effective accessibility testing is a combination of multiple practices such as automated tools, unit tests, manual tests, and user testing.

In the meantime, I challenge you to try out a screen reader by yourself, especially when you build a new custom interactive element from scratch. You’ll discover a new web dimension, and ultimately, it will make you a better web creator.

Things To Keep In Mind For Accessible Fields #

Auto Focusing Invalid Inputs #

Above, I mentioned one possible pattern of automatically focusing the first invalid field, so the user doesn’t need to manually navigate to it. Depending on the case, this pattern might be useful or not. In doubt, I prefer to keep things simple and not add auto-focus. If not obvious, let the user read the summary error message, understand it and then navigate to the field by themselves.

Wrapping Everything Inside <label> #

It might be tempting to wrap everything about a field inside the <label>

element. Well, yes, the assistive technologies would then announce

everything inside automatically on input focus. But, depending on how

‘extensive’ the input is, it might sound more confusing than helpful:

- It’s not clear for screen reader users what exactly the label is.

- If you include interactive elements inside the label, clicking on them might conflict with the automatic input focus behavior.

- In automated tests (e.g., Testing Library), you can’t target an input by its label.

Overall, keeping the label separate from everything else has more benefits, including having grainier control over how elements are announced and organized.

Disabling The Submit Button #

Preventing the user from submitting an invalid form is the most common reason to disable a button. However, the user probably won’t understand why the button is disabled and won’t know how to fix the errors. That’s a big cognitive effort for such a simple task. Whenever possible, avoid disabled buttons. Let people click buttons at any time and show them the error message with instructions. In the last instance, if you really need a disabled button, consider making it an inclusive disabled button, where anyone can understand and interact with it.

Good UX Is Adaptable #

Most physical buildings in the world have at least two ways to navigate them: stairs and lifts. Each one has its unique UX with pros and cons suited for different needs. On the web, don’t fall into the trap of forcing the same pattern on all kinds of users and preferences.

Whenever you find an A11Y issue in a given pattern, try to improve it, but also consider looking for an alternative pattern that can be used simultaneously or toggled.

Remember, every person deserves a good experience, but not every experience is good for everyone.

Wrapping Up #

Field validations are one of those web concepts without dedicated HTML elements that suit modern web patterns, so we need ARIA to fill in the gaps. In short, this article covered the most common attributes for field validations that make a difference for many people in their web journey:

aria-required: To mark a field as required.aria-invalid: To mark the field as invalid.aria-describedby: To connect the description and error message to the input.aria-live: To announce dynamic error messages.

Accessibility is about people, not about ARIA. Besides those attributes, remember to review your colors, icons, field instructions, and, equally important, the validations themselves. Your duty as a web creator is to ensure everyone can enjoy the web, even when a form fails to submit.

Last but not least, I’d like to appreciate the technical review from Ben Mayers, Kitty Giraudel, and Manuel Matuzović. Because sharing is what makes us better. <3

WCAG References #

All the practices we explored in this article are covered by WCAG guideline “3.3 Input Assistance”:

- 3.3.1 Error Identification

- 3.3.2 Labels or Instructions

- 3.3.3 Error Suggestion

- 3.3.4 Error Prevention (Legal)

- 3.3.5 Help

- 3.3.6 Error Prevention

The more I learn about web accessibility, the more I realize accessibility goes beyond complying with web standards. Remember, the WCAG are ‘guidelines’ and not ‘rules’ for a reason. They are there to support you, but if you suspect a guideline doesn’t make sense based on your diverse user research, don’t be afraid to question it and think outside the box. Write about it, and ultimately guidelines will evolve too.