Finding the right typeface for a logo is a challenge and can be a very time-consuming process that requires both creativity and a practical approach. Levi Honing provides the essential background and tools to enhance your typography journey and apply this knowledge to your logo design. Let’s dive deep to learn how to create a logo that is not only expressive but also purposeful and well-thought-out.

Typography is much more than just text on a page — it forms the core of your design. As a designer, I always approach selecting types from two angles: as a creative adventure and as a technical challenge.

Choosing the right typeface for a company, product, or service is an immensely important task. At that moment, you’re not only aligning with the brand’s identity but also laying the foundation to reinforce the company or service’s brand. Finding the right typeface can be a time-consuming process that often begins with an endless search. During this search, you can get tangled up in the many different typefaces, which, over time, all start to look the same.

In this article, I aim to provide you with the essential background and tools to enhance your typography journey and apply this knowledge to your logo design. We will focus on three key pillars:

We will travel back in time to uncover the origins of various typefaces. By exploring different categories, we will illustrate the distinctions with examples and describe the unique characteristics of each category.

Additionally, we will discuss the different font weights and offer advice on when to use each variant. We will delve into letter-spacing and kerning, explaining what they are and how to effectively apply them in your logo designs.

Finally, we will examine how the right typeface choices can significantly influence the impact and success of a brand. With this structured approach, I will show you how to create a logo that is not only expressive but also purposeful and well-thought-out.

Understanding Typography in Logo Design #

From the invention of the Gutenberg press in the mid-15th century through the creation of the first Slab Serif in 1815 and the design of the first digital typeface in 1968, the number of available fonts has grown exponentially. Today, websites like WhatFontIs, a font finder platform, catalogs over a million fonts.

So, the one downside of not being born in the 15th century is that your task of choosing the right font has grown enormously. And once you’ve made the right choice out of a million-plus fonts, there are still many pitfalls to watch out for.

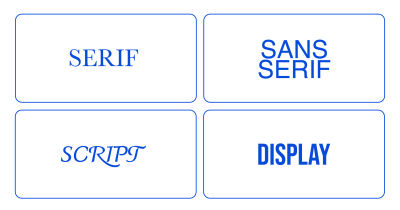

Fortunately for us, all these fonts have already been categorized. In this article, we refer to the following four categories: serif, sans serif, script, and display typefaces. But why do we have these categories, and how do we benefit from them today?

Each category has its specific uses. Serif typefaces are often used for books due to their enhancement of readability on paper, while sans serif typefaces are ideal for screens because of their clean lines. Different typefaces also evoke different emotions: for example, script can convey elegance, while sans serif offers a more modern look. Additionally, typeface categories have a rich history, with Old Style Serifs inspired by Roman inscriptions and Modern Serifs designed for greater contrast.

Today, these categories provide a fundamental basis for choosing the right typeface for any project.

As mentioned, different typefaces evoke different emotions; like people, they convey distinct characteristics:

- Serif fonts are seen as traditional and trustworthy;

- Sans Serif fonts are seen as modern and clear;

- Script fonts can come across as elegant and/or informal depending on the style;

- Display fonts are often bold and dynamic.

Historically, typefaces reflected cultural identities, but the “new typography” movement sought a universal style. Designers emphasized that typefaces should match the character of the text, a view also supported by the Bauhaus school.

Different Fonts And Their Characteristics #

We have touched upon the history of different typeface categories. Now, to make a good font choice, we need to explore these categories and see what sets them apart, as each one has specific characteristics. In this article, we refer to the following four categories:

Let’s take a closer look at each category.

A serif typeface is a typeface that features small lines or decorative elements at the ends of the strokes. These small lines are called “serifs”.

A sans-serif typeface is a typeface that lacks the small lines or decorative elements at the ends of the strokes, resulting in a clean and modern appearance. The term “sans-serif” comes from the French word “sans,” meaning “without,” so sans-serif translates to “without serif.”

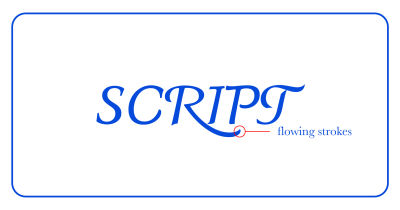

A script typeface is a typeface that mimics the fluid strokes of handwriting or calligraphy, featuring connected letters and flowing strokes for an elegant or artistic appearance.

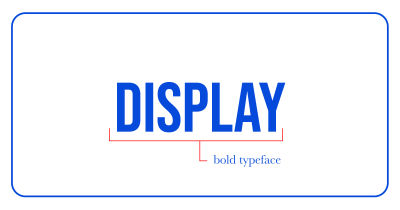

A display typeface is a typeface designed for large sizes, such as headlines or titles, characterized by bold, decorative elements that make a striking visual impact.

Typeface Persona in Practice #

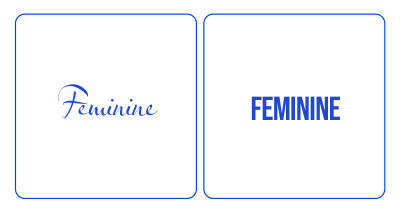

Experts link typeface characteristics to physical traits. Sans serif faces are perceived as cleaner and more modern, while rounded serifs are friendly and squared serifs are more official. Light typefaces are seen as delicate and feminine, and heavy ones are seen as strong and masculine. Some typefaces are designed to be child-friendly with smoother shapes. Traditional serifs are often considered bookish, while sans serifs are seen as modern and no-nonsense.

Based on the provided context, we can assign the following characteristics per category:

- Serif: Bookish, Traditional, Serious, Official, Respectable, Trustworthy.

- Sans Serif: Clean, Modern, Technical, No-nonsense, Machine-like, Clear.

- Script: Elegant, Informal, Feminine, Friendly, Flowing.

- Display: Dramatic, Sophisticated, Urban, Theatrical, Bold, Dynamic.

Let me provide you with a real real-life logo example to help visualize how different typeface categories convey these characteristics.

We’re focusing on ING, a major bank headquartered in the Netherlands. Before we dive into the logo itself, let’s first zoom in on some brand values. On their website, it is stated that they “value integrity above all” and “will not ignore, tolerate, or excuse behavior that breaches our values. To do so would break the trust of society and the trust of the thousands of colleagues who do the right thing.”

Given the strong emphasis on integrity, trust, and adherence to values, the most suitable typeface category would likely be a serif.

The serif font in the ING logo conveys a sense of authority, professionalism, and experience associated with the brand.

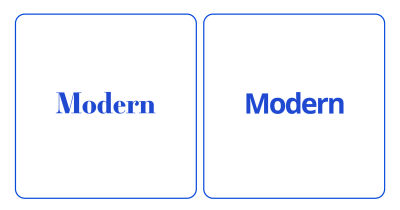

Let’s choose a different font for the logo. The font used in the example is Poppins Bold, a geometric sans-serif typeface.

The sans-serif typeface in this version of the ING logo conveys modernity, simplicity, and accessibility. These are all great traits for a company to convey, but they align less with the brand’s chosen values of integrity, trust, and adherence to tradition. A serif typeface often represents these traits more effectively. While the sans-serif version of the logo may be more accessible and modern, it could also convey a sense of casualness that misaligns with the brand’s values.

So let’s see these traits in action with a game called “Assign the Trait.” The rules are simple: you are shown two different fonts, and you choose which font best represents the given trait.

Understanding these typeface personas is crucial when aligning typography with a company’s brand identity. The choice of typeface should reflect and reinforce the brand’s characteristics and values, ensuring a cohesive and impactful visual identity.

We covered a lot of ground, and I hope you now have a better understanding of different typeface categories and their characteristics. I also hope that the little game of “Assign the Trait” has given you a better grasp of the differences between them. This game would also be great to play while you’re walking your dog or going for a run. See a certain logo on the back of a lorry? Which typeface category does it belong to, and what traits does it convey?

Now, let’s further explore the importance of aligning the typeface with the brand identity.

Brand Identity and Consistency #

The most important aspect when choosing a typeface is that it aligns with the company’s brand identity. We have reviewed various typeface options, and each has its unique characteristics. You can link these characteristics to those of the company.

As discussed in the previous section, a sans-serif is more “modern” and “no-nonsense”. So, for a modern company, a sleek sans-serif typeface often fits better than a classic Serif typeface. In the previous section, we examined the ING logo and how the use of a sans-serif typeface gave it a more modern appearance, but it also reduced the emphasis on certain traits that ING wants to convey with its brand.

To further illustrate the impact of typeface on logo design, let’s explore some more ‘extreme’ examples.

Our first ‘Extreme’ example is Haribo, which is an iconic gummy candy brand. They use a custom sans-serif typeface.

Let’s zoom in on a couple of characteristics of the typeface and explore why this is a great match for the brand.

- Playfulness: The rounded, bold shapes give the logo a playful and child-friendly feel, aligning with its target audience of children and families.

- Simplicity: The simple, easily readable sans-serif design makes it instantly recognizable and accessible.

- Friendliness: The soft, rounded edges of the letters convey a sense of friendliness and positivity.

The second up is Fanta, a global soft drink brand that also uses a custom sans-serif typeface.

- Handcrafted, Cut-Paper Aesthetic: The letters are crafted to appear as though they’ve been cut from paper, giving the typeface a distinct, hand-made look that adds warmth and creativity.

- Expressive: The logo design is energetic and packed with personality, perfectly embodying Fanta’s fun, playful, and youthful vibe.

Using these ‘extreme’ cases, we can really see the power that a well-aligned typeface can have. Both cases embody the fun and friendly values of the brand. While the nuances may be more subtle in other cases, the power is still there.

Now, let’s delve deeper into the different typefaces and also look at weight, style, and letter spacing.

Elements of Typography in Logo Design #

Now that we have a background of the different typeface categories, let’s zoom in on three other elements of typography in logo design:

Typefaces #

Each category of typefaces has a multitude of options. The choice of the right typeface is crucial and perhaps the most important decision when designing a logo. It’s important to realize that often, there isn’t a single ‘best’ choice. To illustrate, we have four variations of the Adidas logo below. Each typeface could be considered a good choice. It’s crucial not to get fixated on finding the perfect typeface. Instead, ensure it aligns with the brand identity and looks good in practical use.

These four typefaces could arguably all be great choices for the Adidas brand, as they each possess the clean, bold, and sans-serif qualities that align with the brand’s values of innovation, courage, and ownership. While the details of typeface selection are important, it’s essential not to get overly fixated on them. The key is to ensure that the typeface resonates with the brand’s identity and communicates its core values effectively. Ultimately, the right typeface is one that not only looks good but also embodies the spirit and essence of the brand.

Let’s zoom in on the different weights and styles each typeface offers.

Weight and Style #

Each typeface can range from 1 to more than 10 different styles, including choices such as Roman and Italic and various weights like Light, Regular, Semi-Bold, and Bold.

Personally, I often lean towards a Roman in Semi-Bold or Bold variant, but this choice heavily depends on the desired appearance, brand name, and brand identity. So, how do you know which font weight to choose?

When to choose bold fonts

- Brand Identity

If the brand is associated with strength, confidence, and modernity, bold fonts can effectively communicate these attributes. - Visibility and Readability

Bold fonts are easy to read from a distance, making them perfect for signage, billboards, and other large formats. - Minimalist Design

Using bold fonts in minimalist logos not only ensures that the logo stands out but also aligns with the principles of minimalism, where less is more.

Letter-spacing & Kerning #

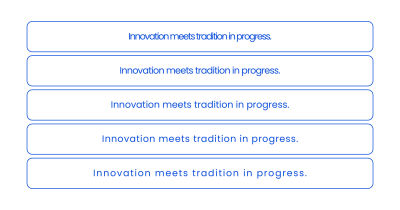

An important aspect of typography is overall word spacing, also known as tracking. This refers to the overall spacing between characters in a block of text. By adjusting the tracking in logo design, we can influence the overall look of the logo. We can make a logo more spacious and open or more compact and tight with minimal adjustments.

Designer and design educator Ellen Lupton states that kerning adjusts the spacing between individual characters in a typeface to ensure visual uniformity. When letters are spaced too uniformly, gaps can appear around certain letters like W, Y, V, T, and L. Modern digital typefaces use kerning pairs tables to control these spaces and create a more balanced look.

Tracking and kerning are often confused. To clarify, tracking (letter-spacing) adjusts the space between all letters uniformly, while kerning specifically involves adjusting the distance between individual pairs of letters to improve the readability and aesthetics of the text.

In the example shown below, we observe the concept of kerning in typography. The middle instance of “LEAF” displays the word without any kerning adjustments, where the spacing between each letter is uniform and unaltered.

In the first “LEAF,” kerning adjustments have been applied between the letters ‘A’ and ‘F’, reducing the space between them to create a more visually appealing and cohesive pair.

In the last “LEAF,” kerning has been applied differently, adjusting the space between ‘E’ and ‘A’. This alteration shifts the visual balance of the word, showing how kerning can change the aesthetics and readability of text (or logo) by fine-tuning the spacing between individual letter pairs.

Essential Techniques for Selecting Typefaces #

Matching Typeface Characteristics with Brand Identity #

As we discussed earlier, different categories of typefaces have unique characteristics that can align well with, or deviate from, the brand identity you want to convey. This is a great starting point on which to base your initial choice.

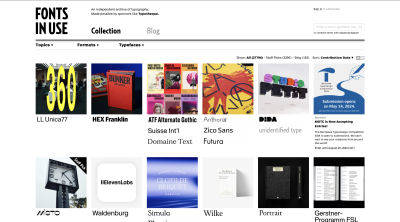

Inspiration #

A large part of the creative process is seeking inspiration. Especially now that you’ve been able to make a choice regarding category, it’s interesting to see the different typefaces in action. This helps you visualize what does and doesn’t work for your brand. Below, I share a selection of my favorite inspiration sources:

Trust the Crowd #

Some typefaces are used more frequently than others. Therefore, choosing typefaces that have been tried and tested over the years is a good starting point. It’s important to distinguish between a popular typeface and a trendy one. In this context, I refer to typefaces that have been “popular” for a long time. Let’s break down some of these typefaces.

Helvetica #

One of the most well-known typefaces is Helvetica, renowned for its intrinsic legibility and clarity since its 1957 debut. Helvetica’s tall x-height, open counters, and neutral letterforms allow it to lend a clean and professional look to any logo.

Some well-known brands that use Helvetica are BMW, Lufthansa, and Nestlé.

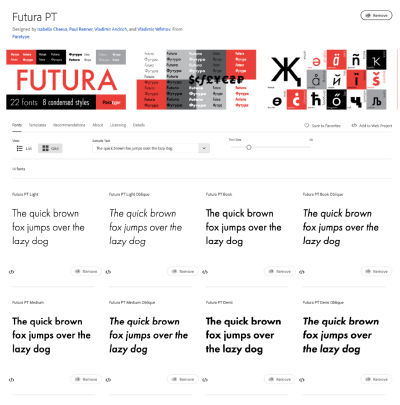

Futura #

Futura has been helping brands convey their identity for almost a century. Designed in 1927, it is celebrated for its geometric simplicity and modernist design. Futura’s precise and clean lines give it a distinctive and timeless look.

Some well-known brands that use Futura are Louis Vuitton, Red Bull, and FedEx.

That said, you naturally have all the creative freedom, and making a bold choice can turn out fantastic, especially for brands where this is desirable.

Two’s Company, Three’s a Crowd #

Combining typefaces is a challenging task. But if you want to create a logo with two different typefaces, make sure there is enough contrast between the two. For example, combine a serif with a sans-serif. If the two typefaces look too similar, it’s better to stick to one typeface. That said, I would never choose more than two typefaces for your logo.

Let’s Build a Brand Logo #

Now that we’ve gone through the above steps, it seems a good time for a practical example. Theory is useful, but only when you put it into practice will you notice that you become more adept at it.

TIP: Try creating a text logo yourself. First, we’ll need to do a company briefing where we come up with a name, define various characteristics, and create a brand identity. This is a great way to get to know your fictional brand.

Bonus challenge: If you want to go one step further, you can also include a logo mark in the briefing. In the following steps, we are going to choose a typeface that suits the brand’s identity and characteristics. For an added challenge, include the logo mark at the start so the typeface has to match your logo mark as well. You can find great graphics at Iconfinder.

Company Briefing #

Company Name: EcoWave

Characteristics:

- Sustainable and eco-friendly products.

- Innovative technologies focused on energy saving.

- Wide range of ecological solutions.

- Focus on quality and reliability.

- Promotion of a green lifestyle.

- Dedicated to addressing marine pollution.

Brand Identity: EcoWave is committed to a greener future. We provide sustainable and eco-friendly products that are essential for a better environment. Our advanced technologies and high-quality solutions enable customers to save energy and minimize their ecological footprint. EcoWave is more than just a brand; we represent a movement towards a more sustainable world with a special focus on combating marine pollution.

Keyword: Sustainability

Now that we’ve been briefed, we can start with the following steps:

- Identify key characteristics: Compile the top three defining characteristics of the company. You can add related words to each characteristic for more detail.

- Match the characteristics: Try to match these characteristics with the characteristics of the typeface category.

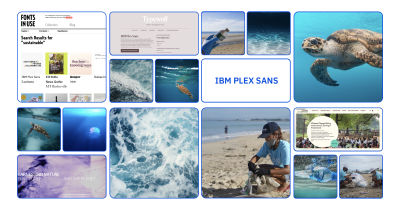

- Get inspired: Check the suggested links for inspiration and search for Sans-Serif fonts, for example. Look at popular fonts, but also search for fonts that fit what you want to convey about the brand (create a mood board).

- Make a preliminary choice: Use the gathered information to make an initial choice for the typeface. Adjust the weight and letter spacing until you are satisfied with the design of your logo.

- Evaluate your design: You now have the first version of your logo. Try it out on different backgrounds and photos that depict the desired look of the company. Assess whether it fits the intended identity and whether you are satisfied with the look. Not satisfied? Go back to your mood board and try a different typeface.

Let’s go over the steps for EcoWave:

1. Sustainable, Trustworthy, Innovative.

2. The briefing and brand focus primarily on innovation. When we match this aspect with the characteristics of typefaces, everything points to a Sans-Serif font, which offers a modern and innovative look.

3. Example Mood Board

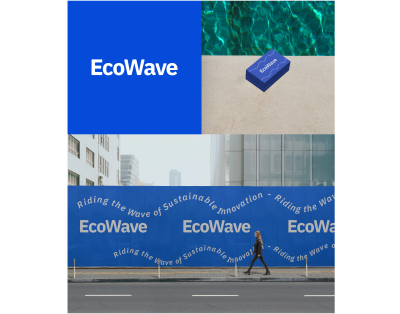

4. Ultimately, I chose the IBM Plex Sans typeface. This modern, sans-serif typeface offers a fresh and contemporary look. It fits excellently with the innovative and sustainable characteristics of EcoWave. Below are the steps from the initial choice to the final result:

IBM Plex Sans Regular

IBM Plex Sans Bold

IBM Plex Sans Bold & Custom letter-spacing

IBM Plex Sans Bold & Custom edges

5. Here, you see the typeface in action. For me, this is a perfect match with the brand’s identity. The look feels just right.

Expert Insights and Trends in Typographic Logo Design #

Those interested in typography might find ‘The Elements of Typographic Style’ by Robert Bringhurst insightful. In this section, I want to share an interesting part about the importance of choosing a typeface that suits the specific task.

“Choose faces that suit the task as well as the subject. You are designing, let us say, a book about bicycle racing. You have found in the specimen books a typeface called Bicycle, which has spokes in the O, an A in the shape of a racing seat, a T that resembles a set of racing handlebars, and tiny cleated shoes perched on the long, one-sided serifs of ascenders and descenders, like pumping feet on the pedals. Surely this is the perfect face for your book?

Actually, typefaces and racing bikes are very much alike. Both are ideas as well as machines, and neither should be burdened with excess drag or baggage. Pictures of pumping feet will not make the type go faster, any more than smoke trails, pictures of rocket ships, or imitation lightning bolts tied to the frame will improve the speed of the bike.

The best type for a book about bicycle racing will be, first of all, an inherently good type. Second, it will be a good type for books, which means a good type for comfortable long-distance reading. Third, it will be a type sympathetic to the theme. It will probably be lean, strong, and swift; perhaps it will also be Italian. But it is unlikely to be carrying excess ornament or freight and unlikely to be indulging in a masquerade.”

— Robert Bringhurst

As Robert Bringhurst illustrates, choosing a typeface should be appropriate not only for the subject but also for the specific task. What lessons can we draw from this for our typeface choice in our logo?

Functional and Aesthetic Considerations #

The typeface must be legible in various sizes and on different mediums, from business cards to billboards. A well-designed logo should be easy to reproduce without loss of clarity.

Brand Identity #

Suppose we have a brand in the bicycle industry, an innovative and modern company. In Robert Bringhurst’s example, we choose the typeface Bicycle, which, due to its name, seems to perfectly match bicycles. However, the typeface described by Robert is a serif font with many decorative elements, which does not align with the desired modern and innovative look of our brand. Therefore, this would be a mismatch.

Trends #

“Styles come and go. Good design is a language, not a style.”

In this part, we discuss some new trends. However, it is also important to highlight the above quote. The basic principles we mention have been applicable for a long time and will continue to be. It can be both fun and challenging to follow the latest trends, but it is essential to integrate them with your basic principles.

Minimalism and Simplicity #

Minimalism in Logo Design remains one of the major trends this year. The most characteristic aspect of this style is to limit the logo to the most essential elements. This creates a clear and timeless character. In typography, this is beneficial for readability and, at the same time, effectively communicating the brand identity in a timeless manner. We also see this well reflected in the rebranding of the fast-food chain Ashton.

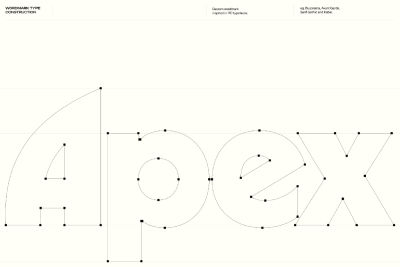

Customization and Uniqueness #

Another growing trend is customization in typography, where designers create personalized typefaces or modify existing typefaces to give the brand a unique look. This can range from subtle adjustments in letterforms to developing a completely custom typeface. Such an approach can contribute to a distinctive visual identity. A good example of this can be seen in the Apex logo, where the ‘A’ and ‘e’ are specifically adjusted.

Conclusion #

We now know that choosing the right typeface for a logo goes beyond personal taste. It has a significant impact on how powerful and recognizable a brand becomes. In this article, we have seen that finding the perfect typeface is a challenge that requires both creativity and a practical approach. With a strong focus on three key aspects:

- Font choice,

- Font weight,

- Letter spacing.

We have seen that finding the right typeface can be a quest, and personal preferences certainly play a role, but with the right tools, this process can be made much easier. The goal is to create a logo that is not only beautiful but also truly adds value by resonating with the people you want to reach and strengthening the brand’s key values.

We also looked at how trends can influence the longevity of your logo. It is important to be trendy, but it is equally important to remain true to timeless principles.

In summary,

“

And for those of you who are interested in diving deeper, I’ve tried to capture the fundamentals we’ve discussed in this article, focusing on good typeface choices, font weights, and letter spacing in a tool huisstijl. While it’s not perfect yet, I hope it can help some people create a simple brand identity that they love.