Web accessibility can be challenging, particularly for clients unfamiliar with tech or compliance with The Americans With Disabilities Act

(ADA). My role as a digital designer often involves guiding clients

toward ADA-compliant web designs. I’ve acquired many strategies over the

years for encouraging clients to adopt accessible web practices and

invest in accessible user interfaces. It’s something that comes up with

nearly every new project, and I decided to develop a personal toolkit to

help me make the case.

Now, I am opening up my toolkit for you to

have and use. While some of the strategies may be specific to me and my

work, there are plenty more that cast a wider net and are more

universally applicable. I’ve considered different real-life scenarios

where I have had to make a case for accessibility. You may even

personally identify with a few of them!

Please enjoy. As you do,

remember that there is no silver bullet for “selling” accessibility. We

can’t win everyone over with cajoling or terse arguments. My hope is

that you are able to use this collection to establish partnerships with

your colleagues and clients alike. Accessibility is something that anyone can influence at various stages in a project,

and “winning” an argument isn’t exactly the point. It’s a bigger

picture we’re after, one that influences how teams work together,

changes habits, and develops a new level of empathy and understanding.

I

begin with general strategies for discussing accessibility with

clients. Following that, I provide specific language and responses you

can use to introduce accessibility practices to your team and clients

and advocate its importance while addressing client skepticism and

concerns. Use it as a starting point and build off of it so that it

incorporates points and scenarios that are more specific to your work. I

sincerely hope it helps you advance accessible practices.

General Strategies #

We’ll

start with a few ways you can position yourself when interacting with

clients. By adopting a certain posture, we can set ourselves up to be

the experts in the room, the ones with solutions rather than arguments.

Showcasing Expertise #

I

tend to establish my expertise and tailor the information to the

client’s understanding of accessibility, which could be not very much.

For those new to accessibility, I offer a concise overview of its

definition, evaluation, and business impact. For clients with a better

grasp of accessible practices, I like to use the WCAG as a point of

reference for helping frame productive discussions based on substance

and real requirements.

Aligning With Client Goals #

I

connect accessibility to the client’s goals instead of presenting

accessibility as a moral imperative. No one loves being told what to do,

and talking to clients on their terms establishes a nice bridge for

helping them connect the dots between the inherent benefits of

accessible practices and what they are trying to accomplish. The two

aren’t mutually exclusive!

In fact, there are many clear benefits for apps that make accessibility a first-class feature. Refer to the “Accessibility Benefits” section to help describe those benefits to your colleagues and clients.

Defining Accessibility In The Project Scope

I

outline accessibility goals early, typically when defining the project

scope and requirements. Baking accessibility into the project scope

ensures that it is at least considered at this crucial stage where

decisions are being made for everything from expected outcomes to

architectural requirements.

User stories and personas are common

artifacts for which designers are often responsible. Use these as

opportunities to define accessibility in the same breath as defining who

the users are and how they interact with the app. Framing stories and

outcomes as user interactions in an “as-when-then-so” format provides an

opening to lead with accessibility:

As a user, when I __________, then I expect that __________, so I can _________.

Fill in the blanks. I think you’ll find that user’s expected outcomes are typically aligned with accessible experiences. Federico Francioni published his take on developing inclusive user personas, building off other excellent resources, including Microsoft’s Inclusive Design guidelines.

Being Ready With Resources and Examples

I

maintain a database of resources for clients interested in learning

more about accessibility. Sharing anecdotes, such as clients who’ve seen

benefits from accessibility or examples of companies penalized for

non-compliance, can be very impactful.

Microsoft is helpful here once again with a collection of brief videos that cover a variety of uses,

from informing your colleagues and clients on basic accessibility

concepts to interviews with accessibility professionals and case studies

involving real users.

There are a few go-to resources I’ve

bookmarked to share with clients who are learning about accessibility

for the first time. What I like about these is the approachable language

and clarity. “Learn Accessibility”

from web.dev is especially useful because it’s framed as a 21-part

course. That may sound daunting, but it’s organized in small chunks that

make it manageable, and sometimes I will simply point to the Glossary to help clients understand the concepts we discuss.

And where “Learn Accessibility” is focused on specific components of accessibility, I find that the Inclusive Design Principles site has a perfect presentation of the concepts and guiding principles of inclusion and accessibility on the web.

Meanwhile, I tend to sit beside a client to look at The A11Y Project.

I pick a few resources to go through. Otherwise, the amount of

information can be overwhelming. I like to offer this during a project’s

planning phase because the site is focused on actionable strategies

that help scope work.

Leveraging User Research

User

research that is specific to the client’s target audience is more

convincing than general statistics alone. When possible, I try to

understand those user’s needs, including what they expect, what sort of

technology they use to browse online, and where they are geographically.

Painting a more complete picture of users — based on

real-life factors and information — offers a more human perspective and

plants the first seeds of empathy in the design process.

Web

analytics are great for identifying who users are and how they currently

interact with the app. At the same time, they are also wrought with

caveats as far as accuracy goes, depending on the tool you use and how

you collect your data. That said, I use the information to support my

user persona decisions and the specific requirements I write. Analytics

add nice brush strokes to the picture but do not paint the entire view.

So, leverage it!

The big caveat with web analytics? There’s no way to identify traffic that uses assistive tech.

That’s a good thing in general as far as privacy goes, but it does mean

that researching the usability of your site is best done with real

users — as it is with any user research, really. The A11Y Project has excellent resources for testing screen readers, including a link to this Smashing Magazine article about manual accessibility testing by Eric Bailey as well as a vast archive of links pointing to other research.

That

said, web analytics can still be very useful to help accommodate other

impairments, for example, segmenting traffic by age (for improving

accessibility for low vision) and geography (for improving performance

gaps for those on low-powered devices). WebAIM also provides insights in a report they produced from a 2018 survey of users who report having low vision.

Leaving Room For Improvements

Chances

are that your project will fall at least somewhat short of your

accessibility plans. It happens! I see plenty of situations where a late

deadline translates into rushed work that sacrifices quality for speed,

and accessibility typically falls victim to degraded quality.

I

keep track of these during the project’s various stages and attempt to

document them. This way, there’s already a roadmap for inclusive and

accessible improvements in subsequent releases. It’s scoped, backlogged,

and ready to drop into a sprint.

For projects involving large sites with numerous accessibility issues, I emphasize that partial accessibility compliance is not the same as actual compliance. I often propose phased solutions, starting with incremental changes that fit within the current scope and budget.

And remember, just because something passes a WCAG success criterion doesn’t necessarily mean it is accessible. Passing tests is a good sign, but there will always be room for improvement.

Commonly Asked Accessibility Questions

Accessibility

is a broad topic, and we can’t assume that everyone knows what

constitutes an “accessible” interface. Often, when I get pushback from a

colleague or client, it’s because they simply do not have the same

context that I do. That’s why I like to keep a handful of answers to

commonly asked questions in my back pocket. It’s amazing how answering

the “basics” leads to productive discussions filled with substance

rather than ones grounded in opinion.

What Do We Mean By “Web Accessibility”? #

When

we say “web accessibility,” we’re generally talking about making online

content available and usable for anyone with a disability, whether it’s

a permanent impairment or a temporary one. It’s the practice of

removing friction that excludes people from gaining access to content or

from completing a task. That usually involves complying with a set of

guidelines that are designed to remove those barriers.

Who Creates Accessibility Guidelines?

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) are created by a working group of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) called the Web Accessibility Initiative

(WAI). The W3C develops guidelines and principles to help designers,

developers, and authors like us create web experiences based on a common

set of standards, including those for HTML, CSS, internationalization,

privacy, security, and yes, accessibility, among many, many other areas. The WAI working group maintains the accessibility standards we call WCAG.

Who Needs Web Accessibility?

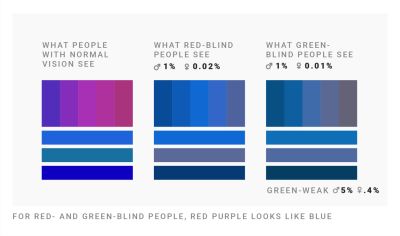

Twenty-seven percent of the U.S. population has a disability, emphasizing the widespread need for accessible web design. WCAG primarily focuses on three groups:

- Cognitive or learning disabilities,

- Visual impairments,

- Motor skills.

When

we make web experiences that solve these issues based on established

guidelines, we’re not only doing good for those who are directly

impacted by impairment but those who may be impaired in less direct ways

as well, such as establishing large target sizes for those tapping a

touchscreen phone with their hands full, or using proper color contrast

for those navigating a screen in bright sunlight. Everyone needs — and

benefits from — accessibility!

Further Reading

How Is Web Accessibility Regulated?

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) is regulated by the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice, which was established by the Civil Rights Act of 1957.

Even though there is a lot of bureaucracy in that last sentence, it’s

reassuring to know the U.S. government not only believes in web

accessibility but enforces it as well.

Non-compliance can result

in legal action, with first-time ADA violations leading to fines of up

to $75,000, increasing to $150,000 for subsequent violations. The number

of lawsuits for alleged ADA breaches has surged in recent years, with

more than 4,500 lawsuits filed in 2023 against sites that fail to comply with WCAG AA 2.1 alone — roughly 500 more lawsuits than 2022!

Further Reading

How Is Web Accessibility Evaluated?

Web

accessibility is something we can test against. Many tools have been

created to audit sites on the spot based on WCAG success criteria that

specify accessible requirements. That would be a standards-based evaluation using WCAG as a reference point for auditing compliance.

WebAIM has an excellent page that compares different types of accessibility testing, reporting, and tooling. They are also quick to note that automated testing,

while convenient, is not a comprehensive way to audit accessibility.

Automated tools that scan websites may be able to pick up instances

where mistakes in the HTML might contribute to accessibility issues and

where color contrasts are insufficient. But they cannot replace or

perfectly imitate a real-life person. Testing in real browsers with real

people continues to be the most effective way to truly evaluate

accessible web experiences.

This isn’t to say automated tools

should not be part of an accessibility testing suite. In fact, they

often highlight areas you may have overlooked. Even false positives are

good in the sense that they force you to pause and look more closely at

something. Some of the most widely used automated tools include the

following:

These are just a few of the most frequent tools I use in my own testing, but there are many more, and the WAI maintains an extensive list of available tools that are worth considering. But again, remember that automated testing is not a one-to-one replacement for testing with real users.

Checklists can be handy for ensuring you are covering your bases:

Accessibility Benefits

When

discussing accessibility, I find the most effective arguments are ones

that are framed around the interests of clients and stakeholders. That

way, the discussion stays within scope and helps everyone see that proper accessibility practices actually benefit business goals. Speaking in business terms is something I openly embrace because it typically supports my case.

The following are a few ways I would like to explain the positive impacts that accessibility has on business goals.

Case Studies

Sometimes,

the most convincing approach is to offer examples of companies that

have committed to accessible practices and come out better for it. And

there are plenty of examples! I like to use case studies and reports in a

similar industry or market for a more apples-to-apples comparison that

stakeholders can identify with.

That said, there are great general

cases involving widely respected companies and brands, including This

American Life and Tesco, that demonstrate benefits such as increased

organic search traffic, enhanced user engagement, and reduced site load

times. For a comprehensive guide on framing these benefits, I refer to

the W3C’s resource on building the business case for accessibility.

What To Say To Your Client

Let

me share how focusing on accessibility can directly benefit your

business. For instance, in 2005, Legal & General revamped their

website with accessibility in mind and saw a substantial increase in

organic search traffic exceeding 50%. This isn’t just about compliance;

it’s about reaching a wider audience more effectively. By making your

site more accessible, we can improve user engagement and potentially

decrease load times, enhancing the overall user experience. This

approach not only broadens your reach to include users with disabilities

but also boosts your site’s performance in search rankings. In short,

prioritizing accessibility aligns with your goal to increase online

visibility and customer engagement.

Further Reading

The Curb-Cut Effect

The

“curb-cut effect” refers to how features originally designed for

accessibility end up benefiting a broader audience. This concept helps

move the conversation away from limiting accessibility as an issue that

only affects the minority.

Features like voice control,

auto-complete, and auto-captions — initially created to enhance

accessibility — have become widely used and appreciated by all users.

This effect also includes situational impairments, like using a phone in

bright sunlight or with one hand, expanding the scope of who benefits

from accessible design. Big companies have found that investing in

accessibility can spur innovation.

What To Say To Your Client

Let’s

consider the ‘curb-cut effect’ in the context of your website.

Originally, curb cuts were designed for wheelchair users, but they ended

up being useful for everyone, from parents with strollers to travelers

with suitcases. Similarly, many digital accessibility features we

implement can enhance the experience for all your users, not just those

with disabilities. For example, features like voice control and

auto-complete were developed for accessibility but are now widely used

by everyone. This isn’t just about inclusivity; it’s about creating a

more versatile and user-friendly website. By incorporating these

accessible features, we’re not only catering to a specific group but

also improving the overall user experience, which can lead to increased

engagement and satisfaction across your entire customer base.

Further Reading

SEO Benefits

I

would like to highlight the SEO benefits that come with accessible best

practices. Things like nicely structured sitemaps, a proper heading

outline, image alt text, and unique link labels not only improve

accessibility for humans but for search engines as well, giving search

crawlers clear context about what is on the page. Stakeholders and

clients care a lot about this stuff, and if they are able to come around

on accessibility, then they’re effectively getting a two-for-one deal.

What To Say To Your Client

Focusing

on accessibility can boost your website’s SEO. Accessible features,

like clear link names and organized sitemaps, align closely with what

search engines prioritize. Google even includes accessibility in its

Lighthouse reporting. This means that by making your site more

accessible, we’re also making it more visible and attractive to search

engines. Moreover, accessible websites tend to have cleaner, more

structured code. This not only improves website stability and loading

times but also enhances how search engines understand and rank your

content. Essentially, by improving accessibility, we’re also optimizing

your site for better search engine performance, which can lead to

increased traffic and higher search rankings.

Further Reading

Better Brand Alignment

Incorporating

accessibility into web design can significantly elevate how users

perceive a brand’s image. The ease of use that comes with accessibility

not only reflects a brand’s commitment to inclusivity and social

responsibility but also differentiates it in competitive markets. By

prioritizing accessibility, brands can convey a personality that is

thoughtful and inclusive, appealing to a broader, more diverse customer

base.

What To Say To Your Client

Implementing

web accessibility is more than just a compliance measure; it’s a

powerful way to enhance your brand image. In the competitive landscape

of e-commerce, having an accessible website sets your brand apart. It

shows your commitment to inclusivity, reaching out to every potential

customer, regardless of their abilities. This not only resonates with a

diverse audience but also positions your brand as socially responsible

and empathetic. In today’s market, where consumers increasingly value

corporate responsibility, this can be a significant differentiator for

your brand, helping to build a loyal customer base and enhance your

overall brand reputation.

Further Reading

Cost Efficiency

I

mentioned earlier how developing accessibility enhances SEO like a

two-for-one package. However, there are additional cost savings that

come with implementing accessibility during the initial stages of web

development rather than retrofitting it later. A proactive approach to

accessibility saves on the potential high costs of auditing and

redesigning an existing site and helps avoid expensive legal

repercussions associated with non-compliance.

What To Say To Your Client

Retrofitting

a website for accessibility can be quite expensive. Consider the costs

of conducting an accessibility audit, followed by potentially extensive

(and expensive) redesign and redevelopment work to rectify issues. These

costs can significantly exceed the investment required to build

accessibility into the website from the start. Additionally, by making

your site accessible now, we can avoid the legal risks and potential

fines associated with ADA non-compliance. Investing in accessibility

early on is a cost-effective strategy that pays off in the long run,

both financially and in terms of brand reputation. Besides, with the SEO

benefits that we get from implementing accessibility, we’re saving lots

of money and work that would otherwise be sunk into redevelopment.

Further Reading

Addressing Client Concerns

Still

getting pushback? There are certain arguments I hear time and again,

and I have started keeping a collection of responses to them. In some

cases, I have left placeholder instructions for tailoring the responses

to your project.

“Our users don’t need it.”

Statistically,

27% of the U.S. population does have some form of disability that

affects their web use. [Insert research on your client’s target

audience, if applicable.] Besides permanent impairments, we should also

take into account situational ones. For example, imagine one of your

potential clients trying to access your site on a sunny golf course,

struggling to see the screen due to glare, or someone in a noisy subway

unable to hear audio content. Accessibility features like high contrast

modes or captions can greatly enhance their experience. By incorporating

accessibility, we’re not only catering to users with disabilities but

also ensuring a seamless experience for anyone in less-than-ideal

conditions. This approach ensures that no potential client is left out,

aligning with the goal to reach and engage a wider audience.

“Our competitors aren’t doing it.”

It’s

interesting that your competitors haven’t yet embraced accessibility,

but this actually presents a unique opportunity for your brand.

Proactively pursuing accessibility not only protects you from the same

legal exposure your competitors face but also positions your brand as a

leader in customer experience. By prioritizing accessibility when others

are not, you’re differentiating your brand as more inclusive and

user-friendly. This both appeals to a broader audience and showcases

your brand’s commitment to social responsibility and innovation.

“We’ll do it later because it’s too expensive.”

I

understand concerns about timing and costs. However, it’s important to

note that integrating accessibility from the start is far more

cost-effective than retrofitting it later. If accessibility is

considered after development is complete, you will face additional

expenses for auditing accessibility, followed by potentially extensive

work involving a redesign and redevelopment. This process can be

significantly more expensive than building in accessibility from the

beginning. Furthermore, delaying accessibility can expose your business

to legal risks. With the increasing number of lawsuits for

non-compliance with accessibility standards, the cost of legal

repercussions could far exceed the expense of implementing accessibility

now. The financially prudent move is to work on accessibility now.

“We’ve never had complaints.”

It’s

great to hear that you haven’t received complaints, but it’s important

to consider that users who struggle to access your site might simply

choose not to return rather than take the extra step to complain about

it. This means you could potentially be missing out on a significant

market segment. Additionally, when accessibility issues do lead to

complaints, they can sometimes escalate into legal cases. Proactively

addressing accessibility can help you tap into a wider audience and

mitigate the risk of future lawsuits.

“It will affect the aesthetics of the site.”

Accessibility

and visual appeal can coexist beautifully. I can show you examples of

websites that are both compliant and visually stunning, demonstrating

that accessibility can enhance rather than detract from a site’s design.

Additionally, when we consider specific design features from an

accessibility standpoint, we often find they actually improve the site’s

overall usability and SEO, making the site more intuitive and

user-friendly for everyone. Our goal is to blend aesthetics with

functionality, creating an inclusive yet visually appealing online

presence.

Handling Common Client Requests

This

section looks at frequent scenarios I’ve encountered in web projects

where accessibility considerations come into play. Each situation

requires carefully balancing the client’s needs/wants with accessibility

standards. I’ll leave placeholder comments in the examples so you are

able to address things that are specific to your project.

The Client Directly Requests An Inaccessible Feature

When

clients request features they’ve seen online — like unfocusable

carousels and complex auto-playing animations — it’s crucial to discuss

them in terms that address accessibility concerns. In these situations, I

acknowledge the appealing aspects of their inspirations but also

highlight their accessibility limitations.

That’s a

really neat feature, and I like it! That said, I think it’s important to

consider how users interact with it. [Insert specific issues that you

note, like carousels without pause buttons or complex animations.] My

recommendation is to take the elements that work well &mdahs;

[insert specific observation] — and adapt them into something more

accessible, such as [Insert suggestion]. This way, we maintain the

aesthetic appeal while ensuring the website is accessible and enjoyable

for every visitor.

The Client Provides Inaccessible Content

This

is where we deal with things like non-descriptive page titles, link

names, form labels, and color contrasts for a better “reading”

experience.

Page Titles

Sometimes,

clients want page titles to be drastically different than the link in

the navigation bar. Usually, this is because they want a more detailed

page title while keeping navigation links succinct.

I

understand the need for descriptive and engaging page titles, but it’s

also essential to maintain consistency with the navigation bar for

accessibility. Here’s our recommendation to balance both needs:

- Keyword Consistency:

You can certainly have a longer page title to provide more context, but

it should include the same key terms as the navigation link. This

ensures that users, especially those using screen readers to announce

content, can easily understand when they have correctly navigated

between pages.

- Succinct Titles With Descriptive Subtitles:

Another approach is to keep the page title succinct, mirroring the

navigation link, and then add a descriptive tagline or subtitle on the

page itself. This way, the page maintains clear navigational consistency

while providing detailed context in the subtitle. These approaches aim

to align the user’s navigation experience with their expectations,

ensuring clarity and accessibility.

Links

A

common issue with web content provided by clients is the use of

non-descriptive calls to action with phrases and link labels, like “Read

More” or “Click Here.” Generic terms can be confusing for users,

particularly for those using screen readers, as they don’t provide

context about what the link leads to or the nature of the content on the

other end.

I’ve noticed some of the link labels say

things like “Read More” or “Click Here” in the design. I would consider

revising them because they could be more descriptive, especially for

those relying on screen readers who have to put up with hearing the

label announced time and again. We recommend labels that clearly

indicate where the link leads. [Provide a specific example.] This

approach makes links more informative and helps all users alike by

telling them in advance what to expect when clicking a certain link. It

enhances the overall user experience by providing clarity and context.

Proper

form labels are a critical aspect of accessible web design. Labels

should clearly indicate the purpose of each input field, whether it’s

required, and the expected format of the information. This clarity is

essential for all users, especially for those using screen readers or

other assistive technologies. Plus, there are accessible approaches to pairing labels and inputs that developers ought to be familiar with.

It’s

important that each form field is clearly labeled to inform users about

the type of data expected. Additionally, indicating which fields are

required and providing format guidelines can greatly enhance the user

experience. [Provide a specific example from the client’s content, e.g.,

we can use ‘Phone (10 digits, no separators)’ for a phone number field

to clearly indicate the format.] These labels not only aid in navigation

and comprehension for all users but also ensure that the forms are

accessible to those using assistive technologies. Well-labeled forms

improve overall user engagement and reduce the likelihood of errors or

confusion.

Brand Palette

Clients

will occasionally approach me with color palettes that produce too low

of contrast when paired together. This happens when, for instance, on a

website with a white background, a client wants to use their brand

accent color for buttons, but that color simply blends into the

background color, making it difficult to read. The solution is usually

creating a slightly adjusted tint or shade that’s used specifically for

digital interfaces — UI colors, if you will. Atul Varma’s “Accessible Color Palette Builder” is a great starting point, as is this UX Lift lander with alternatives.

We

recommend expanding the brand palette with color values that work more

effectively in web designs. By adjusting the tint or shade just a bit,

we can achieve a higher level of contrast between colors when they are

used together. Colors render differently depending on the device and

screen they are on, and even though we might be using colors consistent

with brand identity, those colors will still display differently to

users. By adding colors that are specifically designed for web use, we

can enhance the experience for our users while staying true to the

brand’s essence.

Suggesting An Accessible Feature To Clients

Proactively

suggesting features like sitemaps, pause buttons, and focus indicators

is crucial. I’ll provide tips on how to effectively introduce these

features to clients, emphasizing their importance and benefit.

Sitemap

Sitemaps

play a crucial role in both accessibility and SEO, but clients

sometimes hesitate to include them due to concerns about their visual

appeal. The challenge is to demonstrate the value of site maps without

compromising the site’s overall aesthetic.

I understand

your concerns about the visual appeal of sitemaps. However, it’s

important to consider their significant role in both accessibility and

SEO. For users with screen readers, a sitemap greatly simplifies site

navigation. From an SEO perspective, it acts like a directory, helping

search engines effectively index all your pages, making your site more

discoverable and user-friendly. To address the aesthetic aspect, let’s

look at how major companies like Apple and Microsoft incorporate

sitemaps. Their designs are minimal yet consistent with the site’s

overall look and feel. [If applicable, show how a competitor is using

sitemaps.] By incorporating a well-designed sitemap, we can improve user

experience and search visibility without sacrificing the visual quality

of your website.

Accessible Carousels

Carousels

are contentious design features. While some designers are against them

and have legitimate reasons for it, I believe that with the right

approach, they can be made accessible and effective. There are plenty of

resources that provide guidance on creating accessible carousels.

When

a client requests a home page carousel in a new site design, it’s worth

considering alternative solutions that can avoid the common pitfalls of

carousels, such as low click-through rates, increased load times,

content being pushed below the fold, and potentially annoying

auto-advancing features.

I see the appeal of using a

carousel on your homepage, but there are a few considerations to keep in

mind. Carousels often have low engagement rates and can slow down the

site. They also tend to move key content below the fold, which might not

be ideal for user engagement. An auto-advancing carousel can also be

distracting for users. Instead, we could explore alternative design

solutions that effectively convey your message without these drawbacks.

[Insert recommendation, e.g., For instance, we could use a hero image or

video with a strong call-to-action or a grid layout that showcases

multiple important segments at once.] These alternatives can be more

user-friendly and accessible while still achieving the visual and

functional goals of a carousel.

If we decide to use a

carousel, I make a point of discussing the necessary accessibility

features with the client right from the start. Many clients aren’t aware

that elements like pause buttons are crucial for making auto-advancing

carousels accessible. To illustrate this, I’ll show them examples of

accessible carousel designs that incorporate these features effectively.

Further Reading

Any

animation that starts automatically, lasts more than five seconds, and

is presented in parallel with other content, needs a pause button per WCAG Success Criterion 2.2.2.

A common scenario is when clients want a full-screen video on their

homepage without a pause button. It’s important to explain the necessity

of pause buttons for meeting accessibility standards and ensuring user

comfort without compromising the website’s aesthetics.

I

understand your desire for a dynamic, engaging homepage with a

full-screen video. However, it’s essential for accessibility purposes

that any auto-playing animation that is longer than five seconds

includes a pause button. This is not just about compliance; it’s about

ensuring that all visitors, including those with disabilities, can

comfortably use your site.

The good news is that pause buttons

can be designed to be sleek and non-intrusive, complementing your site’s

aesthetics rather than detracting from them. Think of it like the sound

toggle buttons on videos. They’re there when you need them, but they

don’t distract from the viewing experience. I can show you some examples

of beautifully integrated pause buttons that maintain the immersive

feel of the video while ensuring accessibility standards are met.

Conclusion

That’s

it! This is my complete toolkit for discussing web accessibility with

colleagues and clients at the start of new projects. It’s not always

easy to make a case, which is why I try to appeal from different angles,

using a multitude of resources and research to support my case. But

with practice, care, and true partnership, it’s possible to not only

influence the project but also make accessibility a first-class feature

in the process.

Please use the resources, strategies, and talking

points I have provided. I share them to help you make your case to your

own colleagues and clients. Together, incrementally, we can take steps

toward a more accessible web that is inclusive to all people.

And when in doubt, remember the core principles we covered:

- Show your expertise:

Adapt accessibility discussions to fit the client’s understanding,

offering basic or in-depth explanations based on their familiarity.

- Align with client goals: Connect accessibility with client-specific benefits, such as SEO and brand enhancement.

- Define accessibility in project scope: Include accessibility as an integral part of the design process and explain how it is evaluated.

- Be prepared with Resources: Keep a collection of relevant resources, including success stories and the consequences of non-compliance.

- Utilize User Research: Use targeted user research to inform design choices, demonstrating accessibility’s broad impact.

- Manage Incremental Changes: Suggest iterative changes for large projects to address accessibility in manageable steps.