In this article, Nathan Smith explains how to create modal dialog windows with rich interaction that will only require authoring HTML in order to be used. They are based on Web Components that are currently supported by every major browser.

I have a confession to make — I am not overly fond of modal dialogs (or just “modals” for short). “Hate” would be too strong a word to use, but let’s say that nothing is more of a turnoff when starting to read an article than being “slapped in the face” with a modal window before I have even begun to comprehend what I am looking at.

Or, if I could quote Andy Budd:

That said, modals are everywhere among us. They are a user interface paradigm that we cannot simply disinvent. When used tastefully and wisely, I dare say they can even help add more context to a document or to an app.

Throughout my career, I have written my fair share of modals. I have built bespoke implementations using vanilla JavaScript, jQuery, and more recently — React. If you have ever struggled to build a modal, then you will know what I mean when I say: It is easy to get them wrong. Not only from a visual standpoint but there are plenty of tricky user interactions that need to be accounted for as well.

I am the type of person who likes to “go deep” on topics that vex me — especially if I find the topic resurfacing — hopefully in an effort to avoid revisiting them ever again. When I started to get more into Web Components, I had an “a-ha!” moment. Now that Web Components are widely supported by every major browser (RIP, IE11), this opens up a whole new door of opportunity. I thought to myself:

“What if it were possible to build a modal that, as a developer authoring a page or app, I would not have to fuss with any additional JavaScript config?”

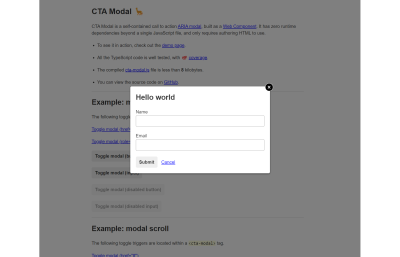

Write once and run everywhere, so to speak, or at least that was my lofty aspiration. Good news. It is indeed possible to build a modal with rich interaction that only requires authoring HTML to use.

Note: In order to benefit from this article and code examples you will need some basic familiarity with HTML, CSS, and JavaScript.

Before We Even Begin #

If you are tight on time and just want to see the finished product, check it out here:

Use The Platform #

Now that we have covered the “why” of scratching this particular itch, throughout the rest of this article I will explain the “how” of building it.

First, a quick crash course on Web Components. They are bundled snippets of HTML, CSS, and JavaScript that encapsulate scope. Meaning, no styles from outside of a component will affect within, nor vice versa. Think of it like a hermetically sealed “clean room” of UI design.

At first blush, this may seem nonsensical. Why would we want a chunk of UI that we cannot control externally via CSS? Hang onto that thought, because we will come back to it soon.

The best explanation is reusability. Building a component in this manner means we are not beholden to any particular JS framework du jour. One common phrase that gets bandied about in conversations around web standards is “use the platform.” Now more than ever, the platform itself has superb cross-browser support.

Deep Dive #

For reference, I will be referring to this code example — cta-modal.ts.

Note: I am using TypeScript here, but you absolutely do not need any additional tooling to create a Web Component. In fact, I wrote my initial proof-of-concept in vanilla JS. I added TypeScript later, to bolster confidence in others using it as an NPM package.

The cta-modal.ts file is chunked apart into several sections:

- Conditional wrapper;

- Constants:

CtaModalclass:- Constructor,

- Binding

thiscontext, - Lifecycle methods,

- Adding and removing events,

- Detecting attribute changes,

- Focusing specific elements,

- Detecting “outside” modal,

- Detecting motion preference,

- Toggling modal show/hide,

- Handle event: click overlay,

- Handle event: click toggle,

- Handle event: focus element,

- Handle event: keyboard;

- DOM loaded callback:

- Waits for the page to be ready,

- Registers the

<cta-modal>tag.

Conditional Wrapper #

There is a single, top level if that wraps the entirety of the file’s code:

The reason for this is twofold. We want to ensure that there is browser support for window.customElements. If so, this gives us a handy way to maintain variable scope. Meaning, that when declaring variables via const or let, they do not “leak” outside of the if {…} block. Whereas using an old school var would be problematic, inadvertently creating several global variables.

Reusable Variables #

Note: A JavaScript class Foo {…} differs from an HTML or CSS class="foo".

Think of it simply as: “A group of functions, bundled together.”

This section of the file contains primitive values that I intend to reuse throughout my JS class declaration. I will call out a few of them as being particularly interesting.

ANIMATION_DURATION

Specifies how long my CSS animations will take. I also reuse this later within asetTimeoutto keep my CSS and JS in sync. It is set to250milliseconds, which is a quarter of a second.

While CSS allows us to specifyanimation-durationin whole seconds (or milliseconds), JS uses increments of milliseconds. Going with this value allows me to use it for both.DATA_SHOWandDATA_HIDE

These are strings for the HTML data attributes'data-cta-modal-show'and'data-cta-modal-hide'that are used to control the show/hide of modal, as well as adjust animation timing in CSS. They are used later in conjunction withANIMATION_DURATION.PREFERS_REDUCED_MOTION

A media query that determines whether or not a user has set their operating system’s preference toreduceforprefers-reduced-motion. I look at this value in both CSS and JS to determine whether to turn off animations.FOCUSABLE_SELECTORS

Contains CSS selectors for all elements that could be considered focusable within a modal. It is used later more than once, viaquerySelectorAll. I have declared it here to help with readability, rather than adding clutter to a function body.

It equates to this string:

Yuck, right!? You can see why I wanted to break that into multiple lines.

As an astute reader, you may have noticed type='hidden' and tabindex="0" are using different quotation marks. That is purposeful, and we will revisit the reasoning later on.

Component Styles #

This section contains a multiline string with a <style>

tag. As mentioned before, styles contained within a Web Component do

not affect the rest of the page. It is worth noting how I am using

embedded variables ${etc} via string interpolation.

- We reference our variable

PREFERS_REDUCED_MOTIONto forcibly set animations tononefor users who prefer reduced motion. - We reference

DATA_SHOWandDATA_HIDEalong withANIMATION_DURATIONto allow shared control over CSS animations. Note the use of themssuffix for milliseconds, since that is the lingua franca of CSS and JS.

Component Markup #

The markup for the modal is the most straightforward part. These are the essential aspects that make up the modal:

- slots,

- scrollable area,

- focus traps,

- semi-transparent overlay,

- dialog window,

- close button.

When making use of a <cta-modal>

tag in one’s page, there are two insertion points for content. Placing

elements inside these areas cause them to appear as part of the modal:

<div slot="button">maps to<slot name='button'>,<div slot="modal">maps to<slot name='modal'>.

You might be wondering what “focus traps” are, and why we need them. These exist to snag focus when a user attempts to tab forwards (or backwards) outside of the modal dialog. If either of these receives focus, they will place the browser’s focus back inside.

Additionally, we give these attributes to the div we want to serve as our modal dialog element. This tells the browser that the <div> is semantically significant. It also allows us to place focus on the element via JS:

aria-modal='true',role='dialog',tabindex'-1'.

You may be wondering: “Why not use the dialog

tag?” Good question. At the time of this writing, it still has some

cross-browser quirks. For more on that, read this article by Scott O’hara. Also, according to the Mozilla documentation, dialog is not allowed to have a tabindex attribute, which we need to put focus on our modal.

Constructor #

Whenever a JS class is instantiated, its constructor function is called. That is just a fancy term that means an instance of the CtaModal class is being created. In the case of our Web Component, this instantiation happens automatically whenever a <cta-modal> is encountered in a page’s HTML.

Within the constructor we call super which tells the HTMLElement class (which we are extend-ing) to call its own constructor. Think of it like glue code, to make sure we tap into some of the default lifecycle methods.

Next, we call this._bind()

which we will cover a bit more later. Then we attach the “shadow DOM”

to our class instance and add the markup that we created as a multiline

string earlier.

After that, we get all the elements — from within the aforementioned component markup section — for use in later function calls. Lastly, we call a few helper methods that read attributes from the corresponding <cta-modal> tag.

Binding this Context #

This is a bit of JS wizardry that saves us from having to type tedious code needlessly elsewhere. When working with DOM events the context of this can change, depending on what element is being interacted with within the page.

One way to ensure that this always means the instance of our class is to specifically call bind.

Essentially, this function makes it, so that it is handled

automatically. That means we do not have to type things like this

everywhere.

Instead of typing that snippet above, every time we add a new function, a handy this._bind() call in the constructor takes care of any/all functions we might have. This loop grabs every class property that is a function and binds it automatically.

Lifecycle Methods #

By nature of this line, where we extend from HTMLElement,

we get a few built-in function calls for “free.” As long as we name our

functions by these names they will be called at the appropriate time

within the lifecycle of our <cta-modal> component.

observedAttributes

This tells the browser which attributes we are watching for changes.attributeChangedCallback

If any of those attributes change, this callback will be invoked. Depending on which attribute changed, we call a function to read the attribute.connectedCallback

This is called when a<cta-modal>tag is registered with the page. We use this opportunity to add all our event handlers.

If you are familiar with React, this is similar to thecomponentDidMountlifecycle event.disconnectedCallback

This is called when a<cta-modal>tag is removed from the page. Likewise, we remove all obsolete event handlers when/if this occurs.

It is similar to thecomponentWillUnmountlifecycle event in React.

Note: It is worth pointing out that these are the only functions within our class that are not prefixed by an underscore (_).

Though not strictly necessary, the reason for this is twofold. One, it

makes it obvious which functions we have created for our new <cta-modal> and which are native lifecycle events of the HTMLElement

class. Two, when we minify our code later the prefix denotes they can

be mangled. Whereas the native lifecycle methods need to retain their

names verbatim.

Adding And Removing Events #

These functions register (and remove) callbacks for various element and page-level events:

- buttons clicked,

- elements focused,

- keyboard pressed,

- overlay clicked.

Detecting Attribute Changes #

These functions handle reading attributes from a <cta-modal> tag and setting various flags as a result:

- Setting an

_isAnimatedboolean on our class instance. - Setting

titleandaria-labelattributes on our close button. - Setting an

aria-labelfor our modal dialog, based on heading text. - Setting an

_isActiveboolean on our class instance. - Setting an

_isStaticboolean on our class instance.

You may be wondering why we are using aria-label

to relate the modal to its heading text (if it exists). At the time of

this writing, browsers are not currently able to correlate an aria-labelledby="…" attribute — within the shadow DOM — to an id="…" that is located in the standard (aka “light”) DOM.

I will not go into great detail about that, but you can read more here:

Focusing Specific Elements #

The _focusElement function allows us to focus an element that may have been active before a modal became active. Whereas the _focusModal function will place focus on the modal dialog itself and will ensure that the modal backdrop is scrolled to the top.

Detecting “Outside” Modal #

This function is handy to know if an element resides outside the parent <cta-modal>

tag. It returns a boolean, which we can use to take appropriate action.

Namely, tab trapping navigation inside the modal while it is active.

Detecting Motion Preference #

Here,

we reuse our variable from before (also used in our CSS) to detect if a

user is okay with motion. That is, they have not explicitly set prefers-reduced-motion to reduce via their operating system preferences.

The returned boolean is a combination of that check, plus the animated="false" flag not being set on <cta-modal>.

Toggling Modal Show/Hide #

There is quite a bit going on in this function, but in essence, it is pretty simple.

- If the modal is not active, show it. If animation is allowed, animate it into place.

- If the modal is active, hide it. If animation is allowed, animate it disappearing.

We also cache the currently active element, so that when the modal closes we can restore focus.

The variables used in our CSS earlier are also used here:

ANIMATION_DURATION,DATA_SHOW,DATA_HIDE.

Handle Event: Click Overlay #

When clicking on the semi-transparent overlay, assuming that static="true" is not set on the <cta-modal> tag, we close the modal.

Handle Event: Click Toggle #

This function uses event delegation on the <div slot="button"> and <div slot="modal"> elements. Whenever a child element with the class cta-modal-toggle is triggered, it will cause the active state of the modal to change.

This includes listening for various events that are considered activating a button:

- mouse clicks,

- pressing the

enterkey, - pressing the

spacebarkey.

Handle Event: Focus Element #

This function is triggered whenever an element receives focus

on the page. Depending on the state of the modal, and which element was

focused, we can trap tab navigation within the modal dialog. This is

where our FOCUSABLE_SELECTORS from early comes into play.

Handle Event: Keyboard #

If a modal is active when the escape key is pressed, it will be closed. If the tab key is pressed, we evaluate whether or not we need to adjust which element is focused.

DOM Loaded Callback #

This event listener tells the window to wait for the DOM (HTML page) to be loaded, and then parses it for any instances of <cta-modal> and attaches our JS interactivity to it. Essentially, we have created a new HTML tag and now the browser knows how to use it.

Build Time Optimization #

I will not go into great detail about this aspect, but I think it is worth calling out.

After transpiling from TypeScript to JavaScript, I run Terser against the JS output. All the aforementioned functions that begin with an underscore (_) are marked as safe to mangle. That is, they go from being named _bind and _addEvents to single letters instead.

That step brings the file size down considerably. Then I run the minified output through a minifyWebComponent.js process that I created, which compresses the embedded <style> and markup even further.

For example, class names and other attributes (and selectors) are minified. This happens in the CSS and HTML.

class='cta-modal__overlay'becomesclass=o. The quotes are removed as well because the browser does not technically need them to understand the intent.- The one CSS selector that is left untouched is

[tabindex="0"], because removing the quotes from around the0seemingly makes it invalid when parsed byquerySelectorAll. However, it is safe to minify within HTML fromtabindex='0'totabindex=0.

When it is all said and done, the file size reduction looks like this (in bytes):

- un-minified: 16,849,

- terser minify: 10,230,

- and my script: 7,689.

To put that into perspective, the favicon.ico

file on Smashing Magazine is 4,286 bytes. So, we are not really adding

much overhead at all, for a lot of functionality that only requires

writing HTML to use.

Conclusion #

If you have read this far, thanks for sticking with me. I hope that I have at least piqued your interest in Web Components!

I know we covered quite a bit, but the good news is: That is all there is to it. There are no frameworks to learn unless you want to. Realistically, you can get started writing your own Web Components using vanilla JS without a build process.

There really has never been a better time to #UseThePlatform. I look forward to seeing what you imagine.

Further Reading #

I would be remiss if I did not mention that there are a myriad of other modal options out there.

While I am biased and feel my approach brings something unique to the table — otherwise I would not have tried to “reinvent the wheel” — you may find that one of these will better suit your needs.

The following examples differ from CTA Modal in that they all require at least some additional JavaScript to be written by the end-user developer. Whereas with CTA Modal, all you have to author is the HTML code.

Flat HTML & JS:

Web Components:

jQuery:

React:

Vue: